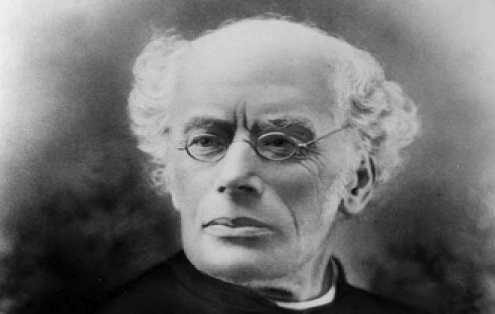

Henry Hawkins

As you learn more about Henry Hawkin’s life and work, you can only feel admiration and reflect on his strong sense of social justice and compassion at a time in history when people experiencing mental distress were more often locked away from society rather than receiving help and support.

Beyond the call of duty

The environment of that time must have been very daunting for Henry Hawkins and he could have been forgiven for losing heart and doing only what he had to do. His religious duties were certainly very important to the patients, several hundred of whom attended the Sunday Service. He also had responsibility for the sad business of funeral services for patients who for some years were buried in the grounds, and introduced markings for their graves which until then were anonymous.

He did much more than his duties required… he befriended patients, read to them, wrote letters on their behalf and helped them in practical ways.

But he did much more than his immediate duties required. He built up the library service so that in one year 2,500 volumes were circulated. This must have meant a great deal to patients, many of whom were confined to their wards or even bedridden. He also increased the number of volunteers in the hospital: they befriended patients, read to them, wrote letters on their behalf and helped them in practical ways, sometimes financially. Even 100 years later it was difficult to attract volunteers for long-stay wards in mental hospitals, and it must have been a difficult task to build up this befriending service, and furthermore to keep it going. There was always a tendency in large asylums and hospitals for such developments to peter out particularly in the face of societal prejudice and the stigma associated with mental distress.

The accomplishment that we celebrate even today is the founding of an After Care Association by Henry, another example of his immense perseverance and persistence.. Various reforms of the asylum-based services were in the air in the era in which he worked. Alas, most either did not get off the ground or did not last and it is extraordinary that the Association he founded, which became Together, has continued for so long.

Some of his principles have survived to today… however poor, ill or forgotten a person may be, they share our common humanity.”

Without doubt, Henry’s personality played a significant part in getting the Association off the ground and to keep it going – from records, he was described as friendly, humorous and modest man who did not seek recognition for himself. He appeared to navigate opposition and negativity with great skill and grace. Henry was certainly a man of principle and was clearly influenced by what was called the Moral Treatment Movement, which is as topical now as it was then. Indeed, the modern Recovery movement, which is very influential in the mental health world today incorporates some of the same principles.

One can say that with Together some of his principles have survived right through to today, although they were often lost elsewhere. The basic principle is that we all share a common humanity: however poor, unwell, or socially isolate or marginalised a person may be, they share our common humanity. That wasn’t an easy position to maintain at that time: there were counter-influences, including misunderstood evolutionary theory – the so-called Social Darwinism of the Victorian polymath Herbert Spencer, with a populist version of his ‘survival of the fittest’. There was a developing fear, hatred even, and denigration of what was called an underclass, a homogenous group amongst whom were included the mentally and physically ill, the poor and criminals.

His practicality was evident from the beginning: work, accommodation, finance; and also friendship.

But Henry Hawkins always managed to maintain an optimistic view, which can be seen in all his writings, and he seems to have deepened his knowledge of patients and their lives over his time at Friern. His practicality is evident in the areas on which the After Care Association concentrated from the beginning: work, accommodation, finances; and also friendship.

He was perhaps influenced by what might have been a lonely childhood, as his only sister was 15 years younger and sadly died at the age of ten, and he was educated at home. He had a large family himself and it seems that Colney Hatch was to some extent like an extended family for him. It was remarkable that that could be the case in those surroundings, but there is no doubt that there was human warmth and altruism even in that setting, amongst both patients and staff.

Not only did Henry leave behind the practical legacy that we see in Together today, from which so many people have benefited though the years, but also an emphasis on the value of human contact and interest. The first name of the Association indicated that it was intended to help ‘friendless’, as well as poor, patients and Henry’s interactions with anyone he came into contact with was one of great personal warmth which he often found reciprocated by the people he was trying to help – even under the horrific experiences of life in an asylum and with the dreadfully severe illnesses of that time, patients were able to give warmth back.